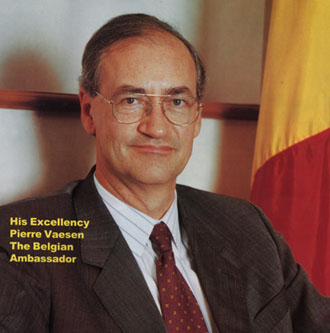

I am today speaking to Pierre Vaesen who, as well as serving Belgium as Ambassador to a number of countries with high migration potential, also served as director of the cabinet of federal minister Armand De Decker. As such he masterminded the Belgian UN initiative of 2006 focusing on migration and development. Following this initiative, the UN Secretary General has called the UN member states to establish a high-level, global dialog on migration and development.

His opinion on and initiatives in multilateral relations forging solutions on European and UN levels have led European diplomacy to new ways of dialogue and peace stabilisation in the world. His unique experience as a diplomat in Poland, Senegal, the United Kingdom and Morocco and later as an Ambassador in Lome, Bangkok, Athens, Kiev and New Delhi gave him a unique insight into world affairs. His position as head of cabinet of the federal minister for cooperation and development, linking and coordinating the work between foreign affairs and interior security and the European Union have further widened the scope of his diplomatic experience on a multilateral level.

The following questions have been broached by Peter von Bethlenfalvy, Executive Director, CEIPA, in discussion with Ambassador Pierre Vaesen in collaboration with Heather Fermor, Senior Policy Adviser, CEIPA.

The total EU development aid in 2022, including mainly non-refundable subsidies to developing countries, is said to amount to over 23 billion euros. Furthermore, the developing countries in need of humanitarian assistance are benefiting from an EU budget of over 10 billion euros covering the period 2021-2027. A large chunk of these subsidies is being channelled to the countries which are the main source of irregular migration. The EU is collectively the biggest donor for international aid in the world, providing over 50 billion euros a year to help overcome poverty and advance global development.

In fact, during the recent migration influx the EU member states themselves became the main recipients of their own development aid, due to the high accommodation costs for asylum seekers, refugees and irregular migrants. Most of the increase of the development aid is due to the increased costs of hosting and maintenance of migrants in donor countries.

Some 25 billion euros have been spent in the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine, out of which approximately 15 billion euros were allocated for the integration of Ukrainian refugees in the EU countries. In the UK, reportedly, the government spent around a third of its development aid budget, £3.7 billion, for housing, medical care and social assistance of refugees, asylum seekers and migrants. That represents more than the UK’s bilateral aid for Africa and Asia combined.

In 2022 there were 330,000 illegal entries into the EU which were registered by Frontex. In the first half of 2022, 179,600 non-EU citizens were ordered to leave the EU Member States, while a total of 33,600 were returned to a non-EU country following an order to leave. This was a costly affair as the majority were assisted returns.

– Would you say that there is a link and interdependence between development aid and migration issues?

First let me explain that I will express here a personal opinion. Being now retired, I am relieved to be able to express my own independent views, without having access to archives and documents from the time of my active diplomatic service. Nevertheless, I will try to be as accurate as possible!

Indeed, there is an obvious link between development and migration, in particular irregular migration. Most of the illegal migrants are trying to come to Europe because of the dramatic social and economic situation in their home countries, while refugees as defined by the Geneva Refugee Convention of 1951 and its Protocol of 1964 belong to a completely different group.

It is well understood, that people would not risk their life undertaking such a hazardous journey, crossing deserts and oceans, being at the mercy of unscrupulous traffickers, if they were not desperate to flee hunger and misery in their home countries.

This means that helping some countries to strengthen their economic and social stability would surely contribute to reducing the migration pressure.

My contribution to the 2006 UN Initiative was the result of a “team’s work “, a combination of several talents and strong motivations.

First, at the Belgian level, we were privileged to have the Federal Minister De Decker, a statesman with clear political vision on our side. Unfortunately, we see less and less politicians today being able to follow their convictions for the good of people. We had also a talented diplomat on our side, namely my colleague Régine De Clerck, Belgian Ambassador for the migration issues, who was instrumental in preparing and launching the UN Migration and Development Initiative. This interplay within the Federal Ministry for Development, in collaboration with the federal ministries of foreign affairs and the interior, while mobilising a wide spectrum of actors amongst the civil society, international and European organisations, academia as well as policy makers in Europe, has led to a success.

– Would you say that the European Commission and the EU member states missed the opportunity to develop a sustainable policy integrating migration into the development aid and vice versa?

I think we have to recognize that we simply failed to set up a coherent and efficient migration policy in the European Union. As you know, since 1974, most European countries have adopted a ” zero migration policy”. There are practically very few legal channels for migrating to Europe, except via the family reunification mechanism or in very narrowly applied recruitment procedures according to economic needs. It sounds strange when you look at the demographic decline in Europe and the real lack of manpower in many segments of the private sectors. At the same time, Europe experiences an increasing flow of illegal migrants remaining in obscure situation and without the possibility of returning them to their countries of origin. Without migration policy there is no efficient interplay and nexus between migration and development aid.

– Has Europe missed its opportunity to set a clear migration agenda with development countries? What about the new European Pact on Migration and Asylum?

Yes, till now, we have failed to establish a clear migration agenda offering some limited but positive prospects for a legal migration. The problem is not at the level of the European institutions but at the leadership of our 27 EU member states, unable to achieve a political consensus in setting the basis for a coherent migration policy. We have to be realistic, there is little chance things will move positively at that level in the near future. The only option is probably to build a common position between the EU member states willing to go forward. We have succeeded in initiating the Schengen process with a few countries on board and then extending it to an acquis communautaire. The same is true with the introduction of the EURO. Once we are able to offer some prospects of legal migration, even if limited, we will reduce the pressure of the illegal migration and the influence of smugglers and traffickers, who presently exert a sort of “monopoly” over migration. In that sense, the European Union’s pact on migration and asylum, that is now being processed through the European institutions and should be completed by the spring of 2024, offers significant progress creating the basis for future voluntary and solidarity mechanisms. This will eventually help assist with crisis management and improve the cooperation in search and rescue operations. The European Asylum Agency shall offer new tools to support the Member States in speeding up their asylum procedures. However, as yet there is no real solution for creating an EU common migration policy. There is still a long way to go! This is my first impression.

– What are the chances of the EU being able to negotiate the quick returns of illegal migrants and rejected asylum seekers to their countries of origin?

We have to distinguish the illegal migrants coming for economic reasons and the asylum seekers being potential refugees as promulgated by the provisions of the Geneva Refugee Convention. The problem is that many economic migrants, knowing that they have no chance to get a work and/or residence permit, apply systematically for asylum in Europe. We have to go on abiding by the rules granting international protection to those who deserve it, like we did with the Syrian refugees in 2015 and the Ukrainians in 2021. Most of them want to return to their countries as soon as the situation goes back to normal, which means as soon as the international or civil war is over. We are then coping with temporary residents.

Let us be honest – not every citizen living under a dictatorship is directly persecuted. Instead, it is people such politicians, journalists, prominent members of the civil society who can be easily identified as politically persecuted individuals. We are obliged to assess the authenticity of the asylum claim within a reasonable delay. Illegal migrants should have the possibility to return to their country of origin. Once Europe has a common and coherent migration policy, opening legal ways to work in our countries, we would experience less illegal migration and fewer problems with returning illegal migrants. Presently, we are witnessing a situation where we have practically no clear ways to accept economic migrants but, at the same time, we are unable to control and prevent illegal migration.

One last point about political asylum: it should be granted to politically persecuted individuals only. The justification of many migrants applying for political asylum by arguing that there is general political repression in their country should not be a reason for granting asylum.

– Is it conceivable that Europe would impose restrictive financial and commercial means to countries refusing to take their nationals back?

I think the European Union should have a global policy towards these countries, including some incentives in order to encourage them to get back their nationals. Europe should also consider reducing or remodelling our development aid programs so as to pressurise governments reluctant to take back their nationals. By all means, we should also have the courage to ask ourselves whether our development aid policies are efficient enough when we are witnessing massive flows of migrants from countries receiving substantial development aid. It should be a priority for the European Union to revise its development aid for countries producing the largest numbers of migrants trying to enter Europe illegally.

– Would, in your opinion, safe African or Asian countries be willing to process migrants and refugees coming from unstable and authoritarian countries in their region, if commitments for strong financial, material and political support to them were given by the EU?

Ideally, this option could be considered. It would only work if the E.U. states and institutions actively participate in helping to achieve a real solution, which means a swift and effective process of the migration applications. This means that we would be willing to accept some applications in both groups – economic migrants and asylum seekers – and that we would contribute financially and logistically to the return of the other ones to their home countries in order to alleviate the burden this solution would represent for the transit countries. Another problem has to be kept in mind – many of these transit countries are not safe, nor are they offering the minimum humanitarian standards required by the international community to adopt this system.

– Wouldn’t this be a less expensive option than keeping irregular migrants in the EU, when you consider the high maintenance costs spent for housing, social assistance and medical care, schooling and educational fees?

The answer is clearly yes, but with the provisos I mentioned in your previous question.

– What is your opinion on one of the recent initiatives of the European Commission, which led to a public humiliation of Europe by Tunisia refunding the EU over 60 million euros while indicating that the request to forcibly hold back migrants from taking boats towards Europe is immoral and cynical?

I believe we could avoid this kind of rebuff in the future if we set up, carefully and without ambiguity, the right procedures, as well as the financial and practical means for their implementation. Also, we cannot forget that some diplomatic and psychological aspects have to be part of our approach – even dictatorships have to take into account their public opinion! Respecting a sense of dignity of our partners and their sensitiveness are also elements of a negotiation, not everything is “technical”.

– Is Islamic and jihadist terrorism in the EU member states, in your opinion, the result of failed immigration, development or international security policy?

I sincerely believe that there are shared responsibilities in our failure to manage a successful immigration process. There was an original sin, if I may say, when we started our labour recruitment in non- European countries in the 1960 ‘s. On both sides, the host countries and the migrants, there was the belief that this move would be temporary and that the migrant workers would return to their countries after a few years, or at maximum after their retirement.

As a consequence, no effort was ever made to help them to integrate into our societies. This was a mistake – most of them stayed in Europe and settled down for good with their families in their host countries. But contrary to the migrants who went to the United States with a strong motivation to adjust permanently to the American “way of life” and values, our migrants in Europe lived mostly “en marge” of the society; socially, linguistically and culturally isolated. It had negative results for the second generation, that were alienated from their countries of origin and at the same marginalised in their host countries. Europe has to revise its integration policy in such a way as to fully take account of the religious and cultural identity of the migrants. Migrant drop outs from schools or those who are socially marginalised may easily become victims of religious fanatism opposing our western values. We easily forget that some liberal western cultural and ethical values about abortion, same sex marriage, euthanasia and so on have only been recently introduced in our legislations and are not even shared by all parts of our “Western” society, and are shared even less so within the migrant groups from North Africa residing in Europe for generations.

What can we do next? There is an in- depth work to start by trying to understand other viewpoints and to initiate a dialogue with these” traditional” and religious groups. It does not mean that we have to compromise on our fundamental values, but rather try to understand and to respect the values of others. However, violence, terrorism and Jihad has no place in our culture and society.

– Would you say that Europe’s democratic foundation is an increasingly attractive option for radicalized Islamists to seek residence instead of staying hidden in their home countries where radical Islamism and Jihadists are severely punished by the state authorities?

There is a paradox when you see fundamentalists expressing their hatred towards the Western values but at the same time enjoying democratic freedoms in Europe. Some declare openly that their aim is to destroy our political systems and to install an Islamist state on our soil. It would be a sort of reverse ” Reconquista”! A dual approach might be useful to cope with this situation; on the one hand a frank and respectful dialogue with the moderates who have other opinions – which is their right as long as they abide by our collective laws as mentioned earlier – and on the other hand , vigorous fight by all legal means – we have to respect ourselves our democratic systems – against the radical militants who are willing to topple by violent means, including terrorism, our constitutional institutions.

– What must be done by EU governments and the EU institutions in order to prevent the further spreading of extremist views which lead to militant Islamism and terrorism in Europe?

Education is the key word to prevent young people from drifting towards extreme and radical views. A European strategy, supported by financial means, could be defined vis a vis schools, universities, media, associations and other useful organs of the civil society. There is a role here for the European Parliament to reflect on this strategy and to formulate some recommendations to the other relevant European institutions, but also to the Member States. Again, we have to keep in mind the very diverse situations in every Member state, that might require different local programs, beyond a common set of principles.

– Subsequently, can one say that in essence large-scale irregular migration undercuts future development policies and aid?

In the long run, irregular migration will have negative implications on our cooperation policies because public opinion will become more and more reluctant to help countries that blatantly appear unable to provide basic services to their citizens, a situation which, unresolved, will generate more and more migration.

– What are the main strategic pillars of development policies which address irregular migration?

I think the most urgent priorities are first to support the population that are working in the traditional sectors (like agriculture) to maintain their activities and improve their livelihood, for example by providing basic services and infrastructures in the rural areas (education, health, local transport). Secondly, we should encourage labour intensive sectors, in order to provide jobs to the unemployed people. Developing an “intelligent” touristic sector, keeping in mind the respect to the local population and the environment, could be helpful in many developing countries.

– Would a consequent re-organisation of the European Foreign services, notably the consular services, help to make them the one stop hub for processing immigration and asylum in requests in the countries of origin and transit of migrants?

There should be a good combination of common European rules and national requirements (immigration quota for each Member state, according to its needs). Logically, once you have a common European strategy, you should have European procedures and services for screening the applications. Let us not be naïve, it will be a difficult exercise. We already see how difficult it is to establish in our Embassies common Schengen offices to deal with the visa applications. Work and residence permits will remain a national competence in the near future. But a close cooperation between our E.U. Embassies / Consulates in the relevant countries could help to limit the uncontrolled moves of illegal migrants and to generate a better “burden sharing” for E.U. Member States willing to accept the asylum seekers.